Filter data

|

ID |

Nickname |

Country / City |

Languages |

Taxonomies |

Comment |

Project / Group |

Map |

|

138668

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

138669

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_MENSENRECHTEN

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

138671

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

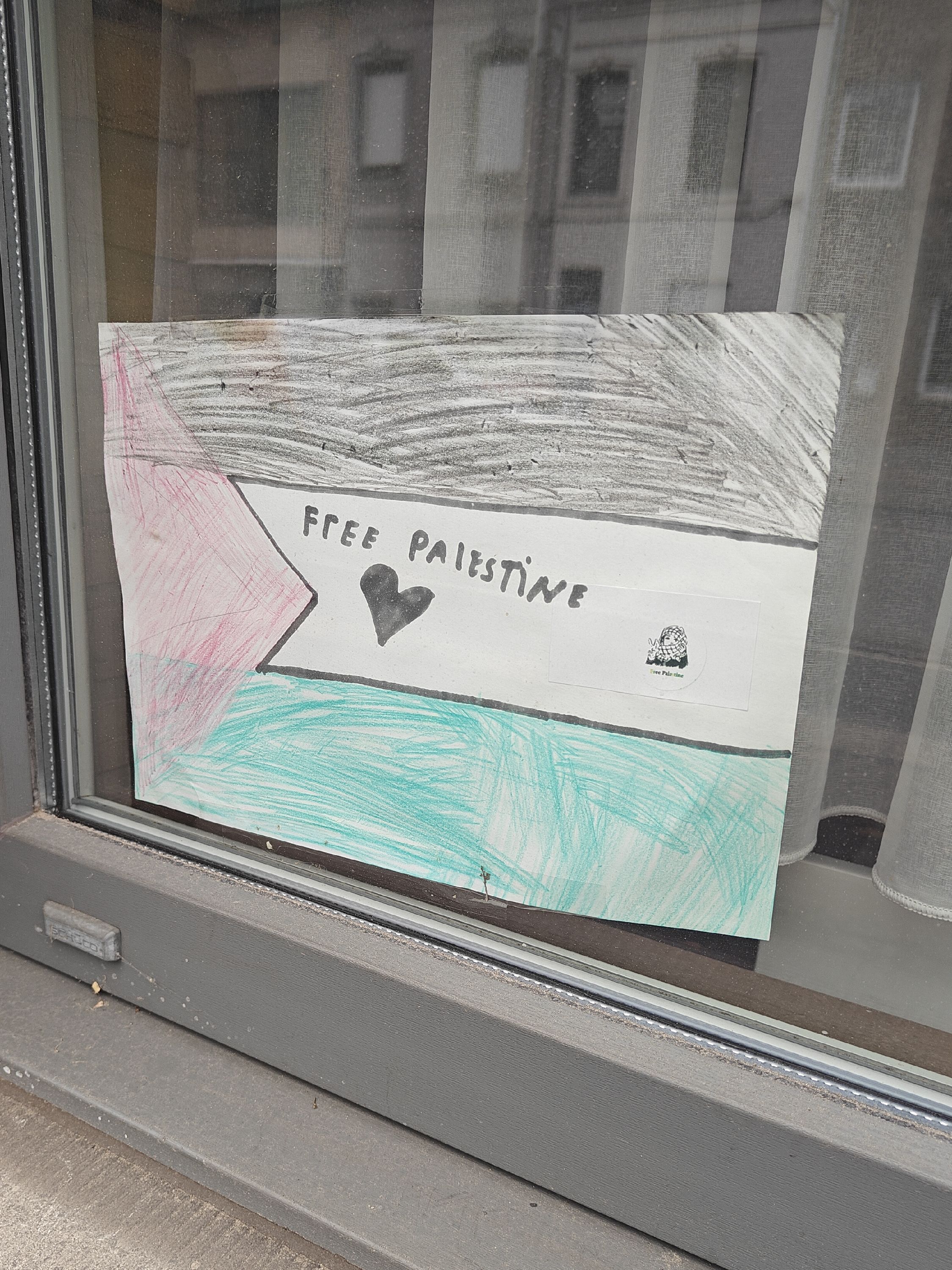

ARSENAAL_PASTINA_BESCHADIGD_LEESBAAR

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

138672

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

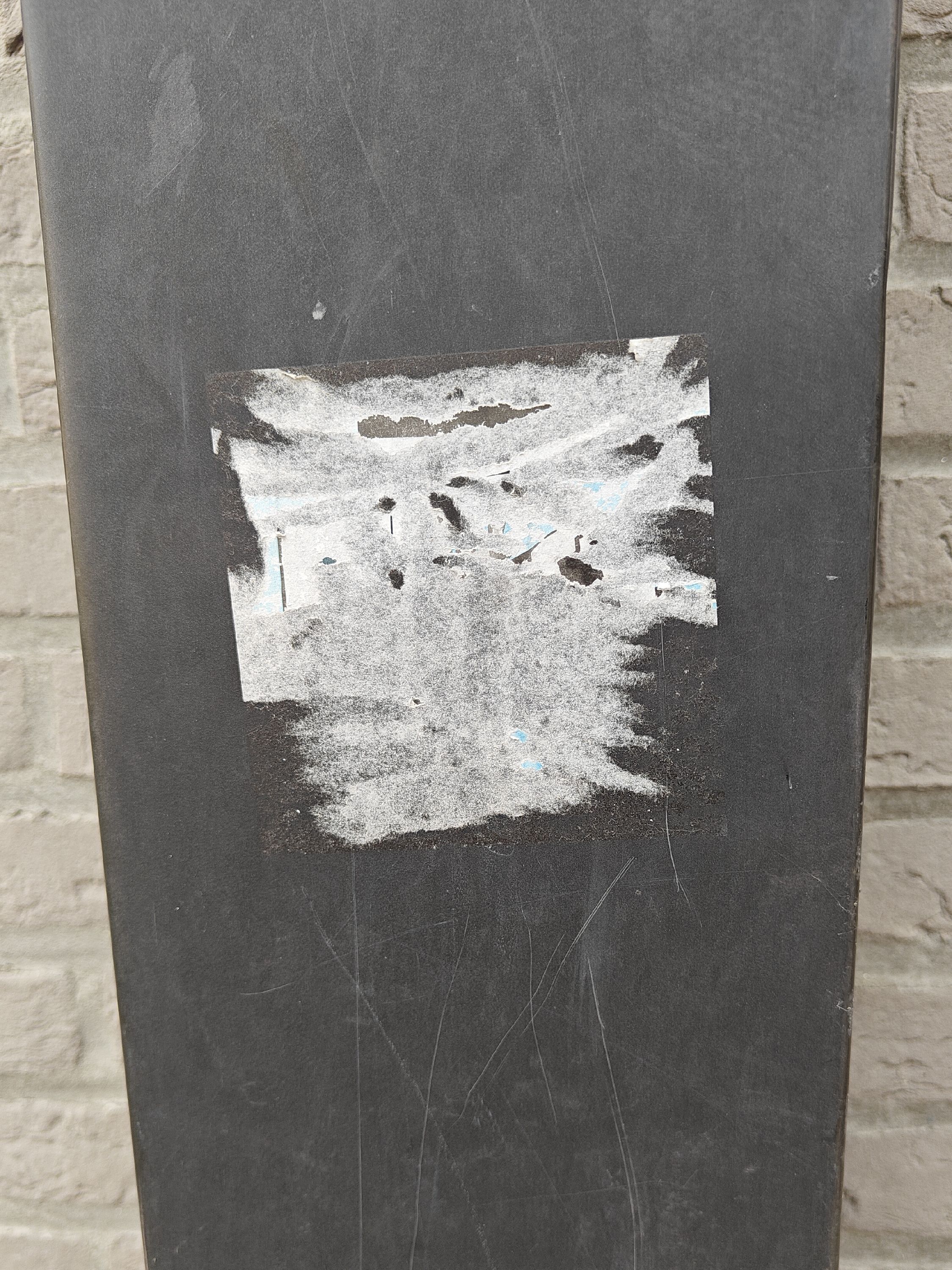

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA_BESCHADIGD_ONLEESBAAR

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139389

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

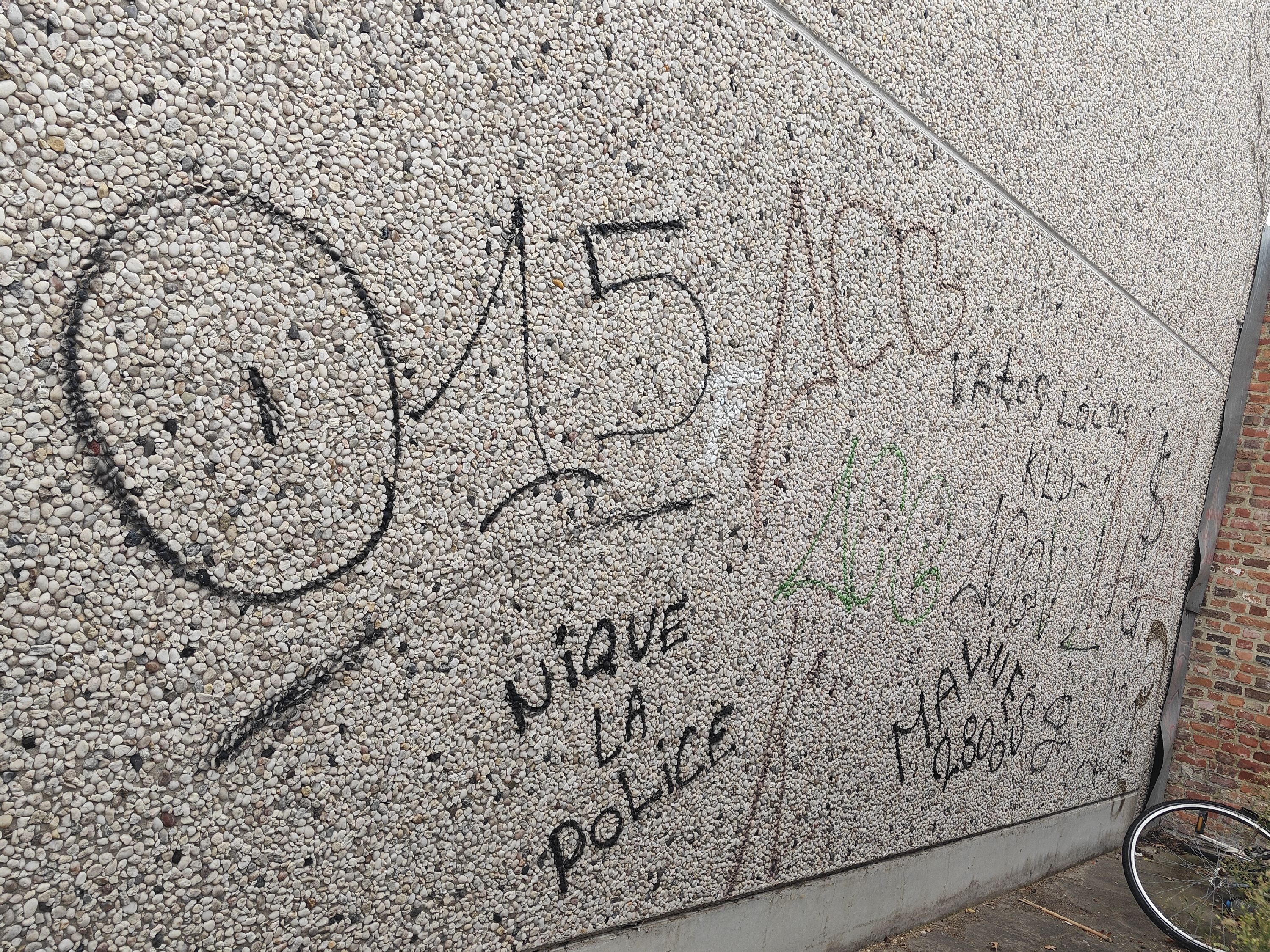

ARSENAAL_RACISME

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139390

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139391

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139392

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

—

|

|

|

|

139393

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139397

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139398

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_ACAB

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139400

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_RACISME

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139401

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA_BESCHADIGD_ONLEESBAAR

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139402

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA_BESCHADIGD_LEESBAAR

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139403

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139404

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_VREDE

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139405

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_MENSENRECHTEN

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139406

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139407

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA_BESCHADIGD_ONLEESBAAR

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|

|

139408

|

Eva_Suetens

|

Belgium

Mechelen

|

|

|

ARSENAAL_PALESTINA

|

MechelenCreativity

|

|